In classical geopolitics, the Monroe Doctrine refers to a power asserting exclusive influence over a region and resisting external or internal challenges to that control. In Nigeri

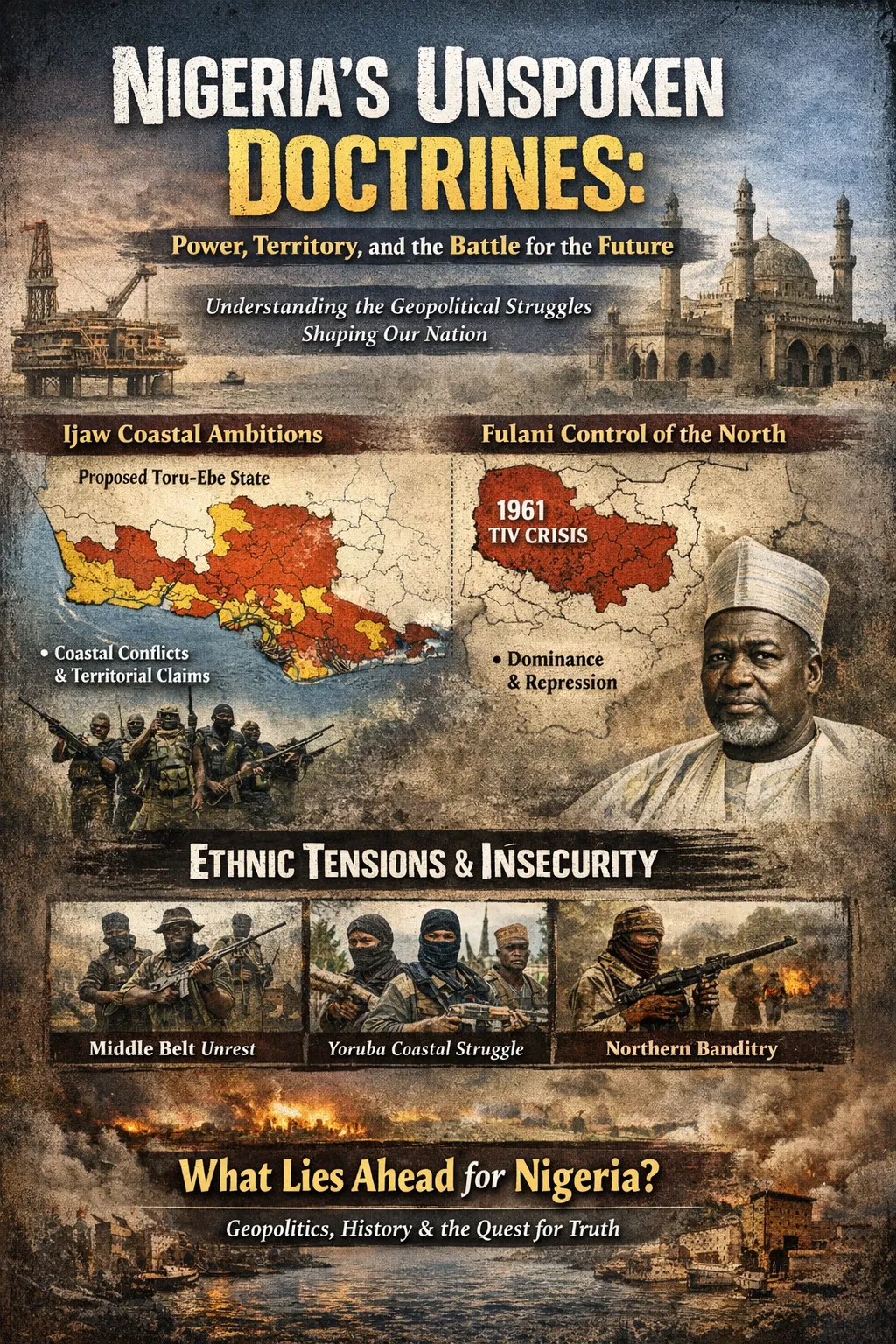

Many Nigerians interpret recurring ethnic tensions as mere “tribal rivalry.” This framing is not only simplistic—it is dangerously misleading. Beneath these conflicts lie long-term geopolitical doctrines, territorial ambitions, and power strategies that have shaped Nigeria’s past and continue to influence its future.

Empires are rarely sustained by weapons alone. More often, they endure through control of narratives, selective ignorance, and the systematic exclusion of historical knowledge. This newsletter series seeks to interrogate these unspoken doctrines, particularly as they affect marginalized and frontline communities.

The Concept of a Local ‘Monroe Doctrine’

In classical geopolitics, the Monroe Doctrine refers to a power asserting exclusive influence over a region and resisting external or internal challenges to that control. In Nigeria, similar doctrines—unofficial but deeply entrenched—have emerged among powerful ethnic and political blocs.

These doctrines are not abstract ideas. They influence political behavior, territorial claims, security responses, and identity suppression. Understanding them is essential for anyone seeking to grasp Nigeria’s structural conflicts.

Case Study I: Ijaw Coastal Doctrine

Among the Ijaw political elite and nationalist thinkers exists a long-standing belief that the entire coastal and creeks region of southern Nigeria falls within Ijaw historical and territorial jurisdiction.

Key ElementsClaims extend across parts of present-day Ondo, Ogun, Lagos, Delta, and Akwa Ibom States

Historical and political confrontations occurred between 1996 and 2003, particularly in coastal Yoruba areas such as Ajegunle and Ilaje

Current tensions persist between Ijaw and Ibibio communities over coastal control in in Akwa Ibom

A striking illustration of this doctrine is the proposed Toru-Ebe State, submitted to the National Assembly. The proposed map incorporates:

The entire Ilaje coastline

Large portions of Itsekiri land and homeland

To critics, this proposal reflects a form of territorial expansionism—comparable to “manifest destiny”—that would likely provoke prolonged multi-ethnic conflict should Nigeria’s federal structure weaken or collapse.

Case Study II: The Northern (Arewa–Fulani) Doctrine

The most institutionalized geopolitical doctrine in Nigeria emerged in the former Northern Region.

Under Ahmadu Bello, often regarded as the architect of modern Arewa political identity, a clear principle was established:

Historical EnforcementPolitical and ideological control of the entire Northern Region must remain firmly in Fulani hands.

In 1961, resistance from the Tiv people—who sought autonomy and political self-determination—was crushed using federal military power

Control of the Niger and Benue river systems

Dominance over fertile Middle Belt lands

Suppression of minority ethnic nationalism

Maintenance of uninterrupted territorial access to Yoruba and Igbo regions

Within this framework, only three identities are broadly tolerated:

Arewa nationalism

Fulani political dominance

Islamic nationalismAlternative ethnic or regional identities—particularly from Middle Belt minorities—are often framed as threats, disloyal, or illegitimate.

Insecurity and the Doctrine of Control

Contemporary insecurity across the Middle Belt and parts of the North cannot be fully understood without acknowledging this doctrine. Armed violence involving groups of Fulani extraction, banditry, and land disputes intersect with long-standing ambitions over territory, identity, and political authority.

This does not imply collective guilt, but it does demand honest discussion of how power hashistorically been exercised—and justified.